Margaret Atwood: Her Background and the Inception of the Terror

So, Margaret Atwood. She is not just some science fiction writer; she’s an absolute intellectual powerhouse and one of Canada’s greatest literary figures, period. Born in 1939, her life spanned the rise of second-wave feminism, the Cold War’s political paranoia, and the explosion of conservative religious movements. All that anxiety? It definitely fueled the creation of the Republic of Gilead. The book dropped in 1985, right in the middle of the Reagan era and a conservative backlash against women’s rights, and it felt totally immediate.

- Atwood’s Rule: She famously stated that she didn’t put anything into the book that hadn’t already happened somewhere in human history. The whole thing the uniforms, the loss of rights is rooted in real-world atrocities and oppressions. That’s why it’s so terrifying.

- Genre Precision: It’s a Speculative Fiction novel (a term Atwood prefers over “science fiction”) and a modern Dystopia. It uses the future (or near-future) as a mirror to critique the present.

The Philosophical Engine: The Warning Hidden in the Red Robes

Atwood’s core philosophy here is a massive, chilling warning about how quickly freedoms can be lost when fear and political extremism combine. The novel is fundamentally an argument about power who has it, how they use language to maintain it, and the total vulnerability of the female body under state control.

| Core Philosophical Theme | What it Means (The Gist of It) |

| Reproductive Control | Gilead’s central driving force is a catastrophic drop in the birth rate. The state responds by literally turning women’s bodies into national resources (vessels for reproduction). It’s the ultimate statement on the stripping of bodily autonomy. |

| The Power of Language | The regime creates Newspeak-like terminology (Handmaids, Commanders, Econowives) to totally flatten complex human relationships into rigid, political roles. Controlling the words controls the thought, man. |

| Feminism as a Warning | The novel isn’t just about men oppressing women; it shows how women can be brutal agents of the patriarchy too (Aunt Lydia, the Wives). It warns against simplistic binary politics. |

| Passive Complicity | Offred (the main character) constantly remembers how the changes started slowly, almost trivially, until it was totally too late to resist. The book forces the reader to confront their own potential passivity. |

When a Book Becomes a Cultural Mirror: Handmaid’s Tale’s Stage Impact

How This Dystopian Vision Influenced Drama and Modern Art

The influence of The Handmaid’s Tale on culture, particularly visual media, is just huge. The iconic visual elements the Handmaid’s bright red robes and the Wives’ blue dresses are instant cultural shorthand for female oppression and resistance. These images are totally powerful and instantly recognizable, making the book perfect for adaptation.

It set a standard for using stark, contrasting uniforms and a highly ritualized, formalized setting to represent totalitarian control, influencing directors across film and TV.

- Visual Symbolism: The contrast between the vibrant red robes (blood, fertility) and the blinding white wings (blinders, forced purity) is one of the most brilliant visual metaphors in modern literature, and it works perfectly on screen.

- Theatrical Tension: The novel uses an intense, internal monologue paired with silent, terrifying external rituals (the Ceremony, the Particicution). This creates an extreme psychological tension that translates brilliantly to the stage and screen.

Key Adaptations: Handmaid’s Tale Across Stages and Screens

The story’s continued relevance means it is constantly being reinterpreted, often with staggering emotional power.

| Adaptation Type | Key Example/Details | Why It’s Famous/Relevant |

| The 1990 Film | Directed by Volker Schlöndorff, starring Natasha Richardson and Faye Dunaway. | An early attempt that tried to capture the atmosphere, though often criticized for lacking the book’s complex internal voice. |

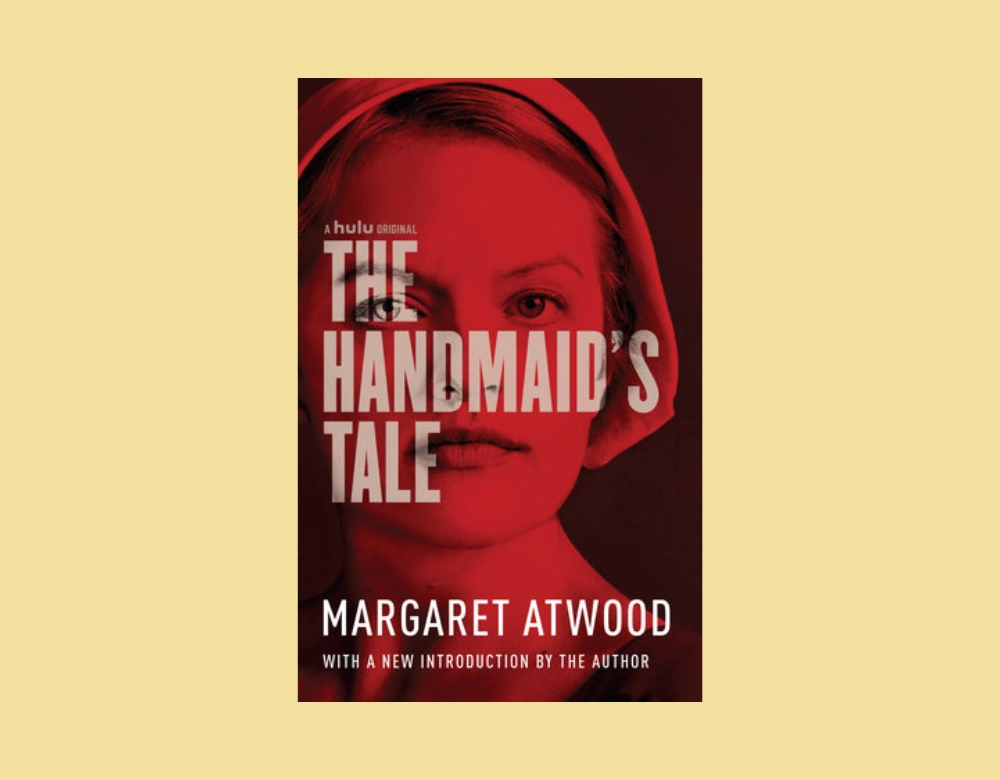

| The Hulu TV Series (2017–Present) | Starring Elisabeth Moss. A massive, critically acclaimed phenomenon. | Became a total cultural touchstone, with the Handmaid costumes used globally in political protests for reproductive rights. It dramatically expanded the world of Gilead beyond Atwood’s original ending. |

| The Royal Opera | Adapted into an opera in 2000. | Proves the text’s enduring dramatic power; the chilling rituals and high-stakes emotional moments work perfectly for the intense, heightened reality of opera. |

Required Reading: Why Atwood’s Warning is Essential

Why University Students Must Grapple with Atwood’s Dystopia

If you are studying political science, gender studies, or modern American literature, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is totally mandatory reading. It is one of the most eloquent, terrifying blueprints for understanding how a Western democracy could actually collapse into a religious autocracy.

It is absolutely crucial for students because:

- Political Science Model: It provides a perfect, terrifying model for analyzing how totalitarian regimes strip rights slowly and through changes to infrastructure and language not just through sudden revolution. That creeping change is the lesson.

- Gender Critique: It is a foundational text for discussing reproductive justice, the patriarchy, and the state’s absolute control over female bodies. It makes abstract political concepts feel intensely personal and physical.

- Narrative Structure (The Historical Notes): The final chapter, written as an academic transcript from the future, totally reframes the entire story, forcing students to question the objectivity of history and who controls the final narrative. That’s a huge critical skill.

What to Read Next: Further Deep Dives into Dystopian Oppression

Once you’ve absorbed the terror of Gilead, you’ll probably want to explore other works that share Atwood’s dark vision of political control and the manipulation of truth.

| Recommended Reading | The Direct Connection to Atwood’s Themes |

| The Testaments (Margaret Atwood) | The direct sequel, published much later. It provides new perspectives (including Aunt Lydia’s) on how Gilead finally fell. It offers crucial context to the original story’s end. |

| Brave New World (Aldous Huxley) | A foundational dystopia. While Handmaid’s Tale controls through fear/pain, Huxley’s world controls through pleasure and distraction. Reading them together gives a full picture of potential control mechanisms. |

| The Children of Men (P.D. James) | Another great novel dealing with a world facing mass infertility, though James focuses on the total collapse of society and hope, rather than Gilead’s rigid, violent restructuring. It shares the fear of human extinction. |

The Unbreakable Hope of the Hidden Word

So, we finish our look at Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Why does this story, more than almost any other modern novel, continue to be shouted about in protests and discussed in classrooms? Because its warning is utterly specific and terrifyingly plausible.

- Atwood permanently showed us that a society can slide into tyranny not with a bang, but with a series of quiet, bureaucratic changes that slowly close every possible door to freedom.

- The book’s final, enduring message is that survival is an act of resistance, and the truest rebellion comes from holding onto memory, connection, and the unwritten, untold story. Nolite te bastardes carborundorum.

It serves as a permanent, chilling vigil against political complacency and the erosion of human rights.